The check that came back

A family’s survival, and how one detail shows the art of telling a lasting story

Some stories write themselves. Others hand their author a blank check to cash in full.

Case in point: the tale of a family who narrowly survived an epochal storm I captured early in my career as a newspaper reporter.

On the 50-year anniversary of the Worcester Tornado, I sat down with the Harvey family of Westborough, MA as they recalled the day in 1953 the sky turned black and nearly everything they owned was lost. Out of the wreckage, one detail—a missing check that turned up weeks later, thirty miles away—became the thread that tied the whole tale together.

It’s the kind of detail that shapes a story, gives it pace and import. And it’s the kind of storytelling that’s shaped my own work ever since: find the human center, follow it to the end and let it speak for itself.

It could be a single surviving anecdote in a storm’s wreckage, or a key insight uncovered through user and market research that anchors product pillars and drives deep user engagement.

This piece, a reminder that the best stories are the ones that capture the most lasting details, was originally published by Herald Media Inc. and Community Newspaper Company, and later in The Milford Daily News. You can also download a PDF of the original newsprint version [available here], alongside the verbatim text reproduced below.

Harveys' harrowing tale

By Geoff Mosher | News Staff Writer

Originally published on June 8, 2003

On the morning of the Worcester Tornado, Robert Harvey took a load of calves to market in Brighton, MA. When he returned home later that afternoon, Harvey placed a check he received as payment on top of the refrigerator. It was the last time he would see the unendorsed check until weeks later.

Around 5:30 p.m., Harvey was bailing hay near the large dairy barn behind his parents' house at 120 South St. when he caught sight of ominous thunderclouds looming above his head. Unaware that a funnel cloud was fast approaching, Harvey raced back to the cinderblock barn. He had a brand new John Deere tractor and didn't want it to get wet.

The 1953 Worcester Tornado cut a path of destruction the likes of which central Massachusetts residents hadn’t experienced in more than 130 years.

“I unhooked the bailer, drove it down into the barn, and I tried to shut the barn doors," Harvey said. "The wind was blowing so hard at that time, I couldn't move them."

After a few moments, he gave up the struggle, ran through the barn, and came out the door at the other end just as the barn was blown away.

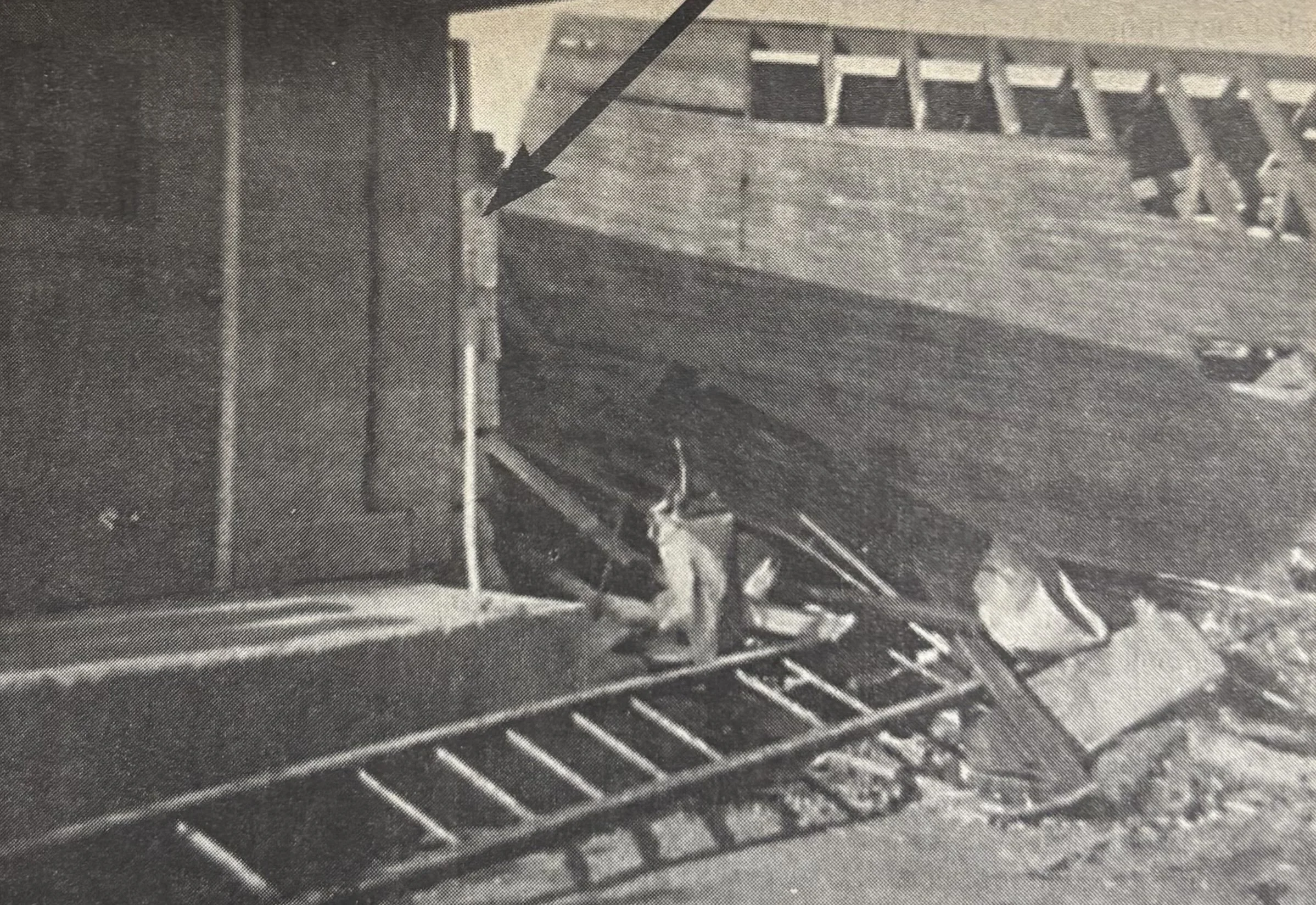

Instinctively, Harvey fell flat an the ground and grabbed hold of an iron post that had been cemented into the steps of the cinderblock milk house to form a railing.

His shirt was torn to shreds, but somehow he didn't have a cut on his body. His new tractor, however, was destroyed, and the barn and his house across the street were flattened. The only part of the milk house that wasn't completely demolished was the corner near the iron post he clung to.

Photo courtesy of the Harvey family

"(The tractor) would have been a lot better if I'd left it outdoors and let it get wet," Harvey said with a laugh.

As soon as the wind subsided, he ran down the street to his father's house. Though still standing, the house was badly damaged; all of the windows and doors were missing. It would later have to be rebuilt. Harvey's brother, Jim, his wife and two children, also lived in the house.

The wind had blown Harvey's mother out of her house, and she landed on a wooden timber with a spike in it. She survived the injury and was later taken to the hospital. Harvey's father, Emory, quickly came to his wife's aid. Once assured that his mother was okay, Harvey then dashed toward his house at 91 South Street.

Harvey's wife, Jane, had just finished preparing supper when it began to get dark outside. She looked out the window and saw a large maple tree uprooted and blown down the driveway.

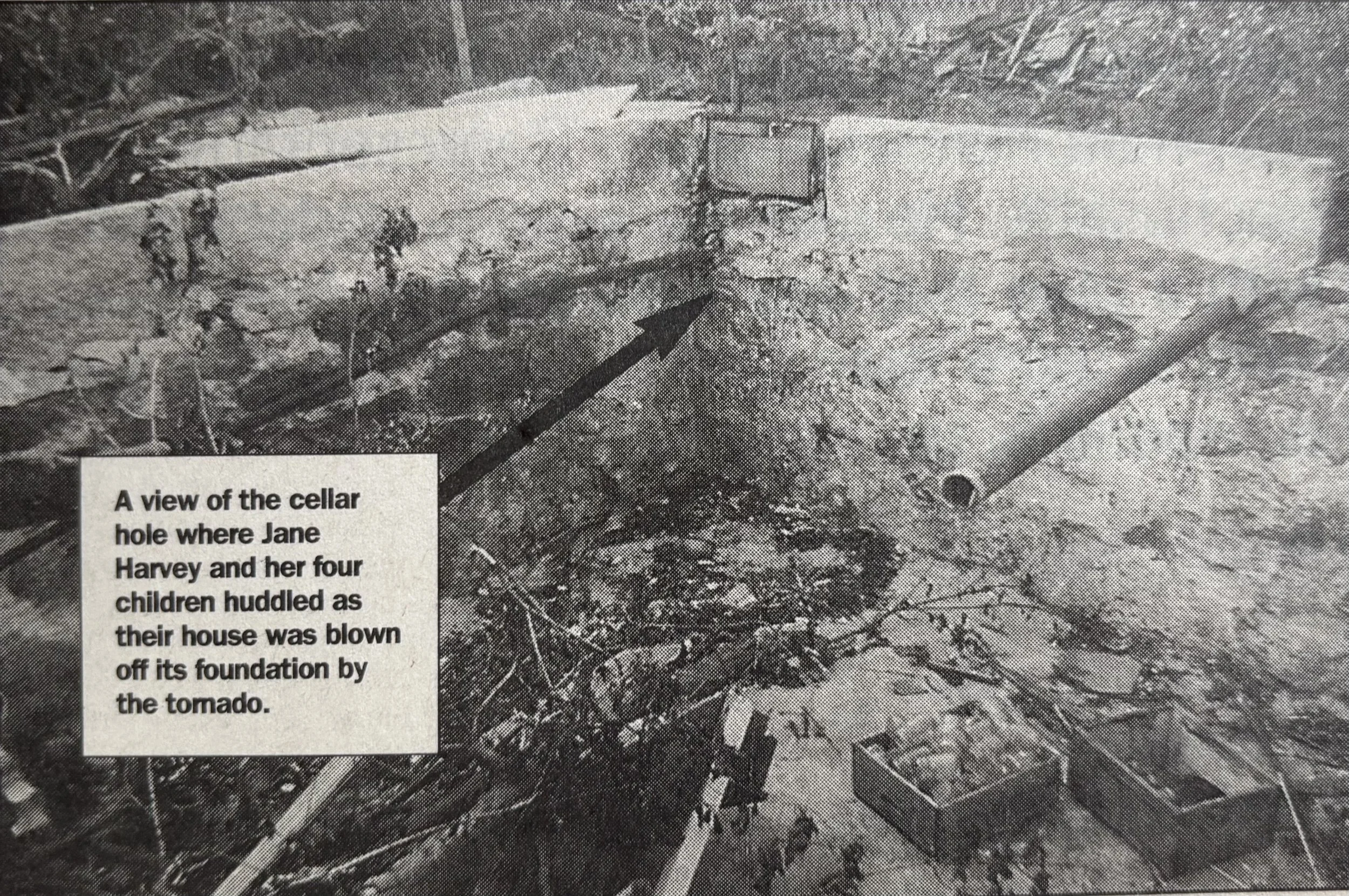

Fearing that the other maple trees on the property might fall on the house, she ordered her three boys—Robert Jr., 9; Bill, 7; and Ben, 4—into the cellar. She followed them carrying her 3-month-old baby, Dorothy. She just reached the bottom of the stairs when the house was blown away.

"We didn't know what had happened," Jane Harvey said in an essay written years later. "We didn't know it was a tornado. It was light again. The wind had stopped blowing. I could hear the hiss of gas escaping from the pipes."

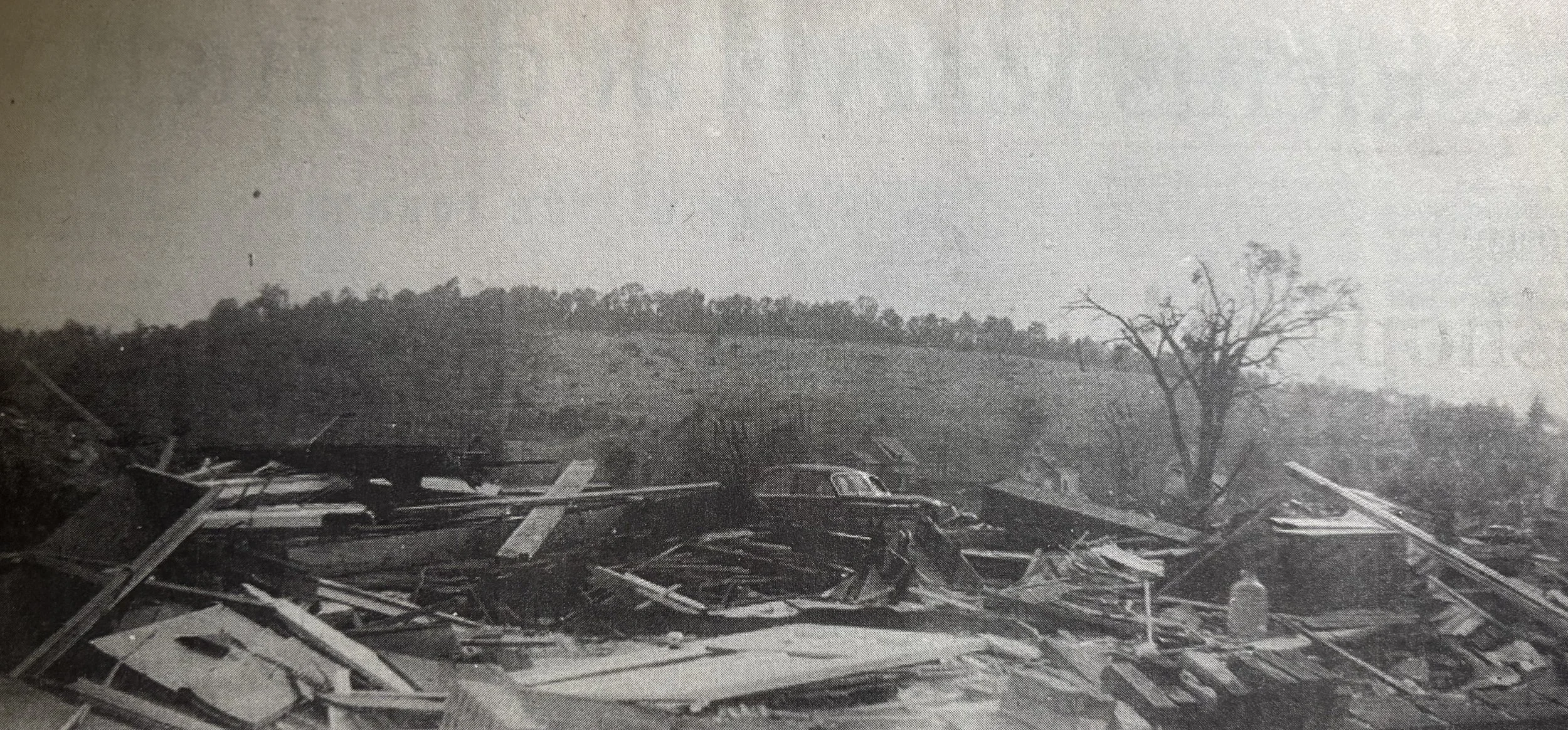

Shirtless from and caked in mud from nearby Ruggles Pond, Robert Harvey arrived at the spot where his house had stood just minutes before. There was nothing left but a cellar hole and a large pile of debris southeast of the house.

Photo courtesy of the Harvey family

In the middle of the wreckage, he noticed the family piano standing upright and still in playable condition. As he approached the cellar hole, Harvey heard his oldest son, Robert Jr., shout, "Hey, Daddy, we're here."

Music to his ears.

"Then he jumped down in the cellar and hugged us all," Jane Harvey said. "We said a prayer of thanks to God because our lives had been saved."

The old cellar was made of large granite slabs that each weighed several tons. All of the slabs had collapsed into the cellar except the three directly above the heads of Harvey's wife and children.

Harvey rebuilt his house on the same spot, around the three slabs he now refers to as the "miracle stones."

Photo courtesy of the Harvey family

Harvey's sister lived nearby and let them stay with her family temporarily, before they moved into the newly-built Kirkside house in town and later into a relative's house in Quonset.

"That night we didn't sleep very much," Jane Harvey said. "All night long the chain saws whined and howled cutting up the trees to clear the road."

The tornado left 12 members of the Harvey family homeless. Relatives and friends sheltered them until new homes were built.

About two-and-half weeks after the tornado ravaged Westborough and left him homeless, Robert Harvey received his missing check in the mail. It had been found 30 miles away in Boston and was still legible.